[Only the first half of the material for this chapter was edited.]

It is not certain where or when the confrontation took place. All we have is Van Helmont’s description. But we do known tensions were high. The name-calling had begun. In print, Van Helmont had accused De Heer of blasphemy. He had denied that Spa waters were sour. He had denied that a spirit could escape from a well-stoppered bottle. In response, De Heer had responded in print calling Van Helmont os inferni (“mouth of Hell”) playing on the literal interpretation in Middle Dutch of Helmont’s surname.

One of Van Helmont’s chief points of contention in this confrontation centered around some special equipment that Van Helmont had designed to prove that air could not be transmuted into water which he claimed De Heer had coopted and misused. De Heer had claimed the apparatus was nothing more than a perpetual motion machine, but Van Helmont replied it was nothing of the kind. In defense of his analytical abilities, De Heer claimed he had been a professor of mathematics in Padua, but Van Helmont demonstrated that De Heer’s failure to understand his apparatus proved De Heer’s ignorance of mathematics. As to how the confrontation ended, memories diverged. Van Helmont claimed that De Heer was struck drumb. De Heer claimed in 1630 that he had totally bested Van Helmont in his original written response to him. 1

The debate between Henri de Heer (1570-1636) and Joan Baptista Van Helmont (1579-1644) was the first of several intense disputes that would impact the development of mineral water analysis in the 17th and 18th centuries. There was a general pattern to these debates. A younger adversary comes along to challenge the respected elder. And, not just to challenge on this point or that point, but to attempt to completely undermine the authority of the elder by rejecting every claim the elder has made. Some of these debates can be seen as argument for argument’s sake, and some undoubtedly were. Some seem simply like personality conflicts, and some undoubtedly were.

But many of these debates have been represented as something much deeper — modern versus traditional, Paracelsan versus anti-Paracelsan, the conflict of competing paradigms. Indeed, the young Van Helmont does seem to model himself on Paracelsus.

Van Helmont’s earliest work, Eisagoge, written between 1599 and 1607 when he was in his twenties, is “a comprehensive survey of Paracelsian Theory, beginning with a dream where the ghost of Paracelsus reveals him his secrets”. 2

According to Paracelsus, knowledge has to be based on the twofold light of God and nature. The earliest physicians, for instance, Hippocrates, were inspired by both. After him, the birth of professional medicine involved the struggle for power and wealth. This caste obscured the light of nature through demonstration more geometrico, by logic, sophisms, and building of theoremata (a loan-word coming from the technical vocabulary of the Greek empiricists).

Galen and Aristotle were responsible for the new kind of medicine, reasoning on diseases instead of healing them. In fact, the only usefulness of medical theory is to support the claims of the medical establishment. 3

Van Helmont could not agree more with this condemnation of Galen and Aristotle.

In his first published work, the essay on the weapon salve published in 1621, Van Helmont openly avows himself a follower of Paracelsus. 4 Having suffered a lot of critics himself, Van Helmont obviously felt a lot of empathy with Paracelsus.

I have sufficiently known the customs of Contradicters: For when they have nothing more of moment to say against the thing it self, they become the more reproachful, and fall foule upon the Man [i.e., Paracelsus]…I answer, as to the Scoffers, and Mocks or Taunts of many showrd’d down on a Man that was the Ornament of Germany, they are not worth a Nut, or not at all to be regarded, and for that very Cause, render the asserter of them the more unworthy. 5

Many later challengers will in turn model themselves on Van Helmont. But in so modeling they did not simply echo their masters as earlier generations. They seem much more focused on simply refuting the opinions of their adversaries on whatever grounds they can muster even if the grounds do not seem totally consistent with their master’s opinions. Indeed, adversaries can often times seem more knowledge of Paracelsus or Van Helmont than the so-called disciple and end us using the arguments of Paracelsus or Van Helmont against the disciple.

Historians of science in the late 20th century have done much to elevate Van Helmont to the heights of Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton, Antoine Lavoisier, and the other fathers of modern science. 6 On the other hand, De Heer earns rarely more than a footnote in the history of science. Yet in the history of science it would be in the clashes, which often drew in not simply the original adversaries but numerous commentators that might keep the clash alive for years afterward, that new approaches to the study of mineral spring water would be hammered out. Whereas for centuries, mineral water analysis had barely moved forward beyond Dioscorides, Archigenes, and Galen, over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries mineral water analysis grew by leaps and bounds, lock step with the rise of modern chemistry.

The Weapon-Salve Cure

The following facts about Joan Baptista Van Helmont (1579-1644) are unanimously accepted by scholars: he was born in Brussels and also died there; he studied at the University of Louvain, from which he initially refused to accept his degree (however, in 1599 he obtained his doctorate there); he travelled extensively across Europe (visiting France, England, Switzerland, and Italy); he was strongly influenced by Paracelsian ideas, which led him to conceive of the universe as ‘an organism in which matter was configured by a series of forces’ — however, he rejected Paracelsus’s tria prima (mercury, salt, and sulphur); he believed that water is the universal element that constitutes all things natural; between 1609-1616 he retired to Vilvoorde to dedicate himself to an intense study of pyrotechnia; and, lastly, he coined the term gas (the spiritus sylvestri that was produced when burning charcoal), which he mostly likely derived from the Greek chaos“. 7

By the time of Van Helmont’s attack on de Heer, he had already developed a bad boy image. With Paracelsus as a model, Van Helmont was bound to get in trouble with the powers that be and the established order. 8 And it would first and foremost come to the fore when Van Helmont jumped to the defense of Paracelsus’ weapon-salve cure.

Debate over the weapon-salve cure flared up in the early in 17th century. Rudolph Goclenius (1572-1628), Protestant Professor of Philosophy at Marburg, published works in 1608 and 1613 ascribing the effect of the salve to pure natural causes. The Jesuit Jean Roberti (1569-1651), a Jesuit casuist and Professor at Douai, Trier, Würzburg, and Mainz, challenged Goclenius on the grounds that any form of magic was the work of the devil. The two were off to the races in a literary duel that would result in seven treatises over the course of ten years (1615-1625). 9

Van Helmont took the attitude of the unprejudiced observer who collects all available case-reports, and wanted to give the method every chance to be proven. He found fault with both contenders, criticising Goclenius’s factual evidence and Roberti’s appraisal of the phenomenon as a whole. The former had omitted the presence of inspissated blood on the weapon, which in Van Helmont’s opinion was essential for the method to be effective. Moreover, Goclenius’s contention that the moss which was an ingredient of the salve must come from the skull of a hanged criminal was not true; any skull would be suitable. Roberti, on the other hand, had looked for his arguments in a field that was most unproducitve for the natural philosopher, namely theology in general and action of the devil in particular. He had treated a problem of natural science as a quaestio juris rather than a quaestio facti as it should be.

In Van Helmont’s view the reported effects were amenable to explanation in naturalistic terms. They were indeed attributable to ‘magnetic’ forces, to attraction, that is, of particles; in the present instance, particles of the ointment mixed with blood sticking to the weapon were attracted to the wound. 10

Unfortunately, like Paracelsus, Van Helmont’s approach was one almost designed to antagonize nearly everyone. Paracelsians could be critized for too closely following Paracelsus contrary to the evidence. Traditional physicians could be criticized for too closely following Aristotle and Galen contrary to the evidence. Jesuits could be criticized for too closely following Church orthodoxy contrary to the evidence. And everyone could be criticized for not interpreting the Bible correctly. And as a naturalist and a good Catholic, Van Helmont always seemed to know better how to interpret nature and the Bible better than anyone else.

Antagonizing other physicians could ostracize Van Helmont socially and professionally, but openly critizing and even ridiculing Jesuits at a time when the Inquisition was in full swing and Belgium was “in the throes of the Spanish occupation with all its attendant cultural and doctrinal convulsions” could be potentially fatal. 11 “This was, incidentally, the age of witchhunts, particularly between 1592 and 1625” 12

Ecclesiastical prosecution followed soon upon publication of Van Helmont’s Magnetic Cure of Wounds in Paris in 1621, prosecution which would end up lasting some twenty years.

In 1623 members of the Louvain Medical Facuty denounced Van Helmont’s tract as a ‘monstrous pamphlet. In 1625 the General Inquisition of Spain declared twenty-seven of its propositions as suspect of heresy, as impudently arrogant, ans as affiliated to Lutheran and Calvinist doctrine. A year later the tractr was impounded by order of Sebastian Huerta at Madrid. In 1627 Van Helmont affirmed his innocence and submitted to ecclesiastical discipline before the curia of Malines, which referred the matter to the Louvain Theological Faculty. In 1630 the defendant admitted his guilt and revoked his ‘scandalous pronouncements’, to be duly convicted by the Faculty for adhering to the monstrous superstitions of the school of Paracelsus, that is of the devil himself, for ‘perverting nature by ascribing to it all magic and diabolic art and for having spread more than Cimmerian darkness all over the world by his chemical philosophy [pyrotechnice philosophando]’. 13

Van Helmont’s house arrest was finally ended in 1636 and formal proceedings against him officially discontinued in 1642, two years before his death.

Beginnings of the Spa Debate

While Van Helmont was still wrapped up in his troubles with the Church over the weapon-salve cure, he jumped into another controversy over Spa waters. The controversy began in 1624 when Van Helmont published Supplementum de Spadanis fontibus (Liége, 1624) which directly attacked De Heer’s popular Spadacrene, which had just been republished in a new Latin edition in 1622. 14

In the pamphlets, Van Helmont actually does not mention de Heer by name, but he lambasts “a certain Author, of the Fountains of the Spaw” who could be none other than de Heer because Van Helmont criticizes pretty much every major assumption and conclusion in De Heer’s Spadacrene.

De Heer’s Argument

Van Helmont started off with an attack on De Heer’s theory of the origins of fountains on the grounds of blasphemy. De Heer, in line with many other 16th- and 17th-century writers, attempted to incorporate both biblical and Aristotelian elements in his theory of fountains. He begins with the Book of Genesis: “We can not doubt, that when God in the third day of Creation of the Universe divided the waters of the earth, and placed them in fixed & determined locations.” De Heer then conjectures that God then made these surface waters “pass by secret issues in the bosom of the earth so that by their aid the formation of metal could happen”, providing a divine spin to another contemporaneous theory on the aqueous origins of metals. As to the origin of fountains, De Heer then supposes that all the fountains have drawn their origins from these clusters of groundwater, the same as those which God adorned the earth from the beginning of the World, in order to contribute to the beauty & perfection of His work, in order to provide for the needs of Adam. 15

Having just laid down a biblical origin seemingly for all springs, De Heer then proceeds to undermine it in favor of an Aristotelian explanation. He notes that Aristotle, in his Meteorology, claimed that “the fountains & rivers come from the air which is enclosed in the bowels of the earth, which is transformed by the cold into water in these underground caverns”. De Heer notes that obviously Aristotle’s theory could not explain the four rivers that went out from the Garden of Eden, of which Aristotle probably had no knowledge and which would not wait for air to be changed into water in order to be formed & to flow. However, De Heer believed that there were several fountains formed in Aristotle’s time and in his own time that did originate in the way Aristotle claimed.

In support of this Aristotelian theory, De Heer observes that “the vapors which are elevated to the average region of the air change by the cold into water of the place where they are” and by logical extension “it is quite natural to believe that the exhalations that rise from the depths of the earth, are also transformed by the cold into water, and gradually penetrate areas that contain them.” Furthermore this Aristotelian theory better explains the difference among fountains. “This is because when these waters are formed in underground filled with sharp rocks, hard, high, they produce clear fountains; if on the contrary they are muddy, they are not as salty, and show the effects of the ground under which they have flowed in the earth.”

In addition, De Heer believes that Aristotle’s theory helps better explains the difference between cold and hot fountains. Cold fountains form from extremely cold vaporous air. Hot fountains are made from exhalations so hot, that the seeds of insects that are met there, have the power to germinate & achieve full maturity. This is why we sometimes see small toads, frogs and other animals fall with the rain. The cause of hot and cold fountains comes therefore equally from exhalations, which are found in the places where they flow underground. 16

Van Helmont’s Refutation

Van Helmont believed that de Heer’s theory was first and foremost wrong on scriptural grounds. For Van Helmont, the Bible was sufficient to explain the origins of natural phenomena like fountains. “For this as for almost all his arguments Van Helmont finds a scriptural basis”. 17 But what seemed to aggravate Van Helmont even more was the egregious way that writers like De Heer so freely turned to Aristotle to modify or supplement explanations which Van Helmont believed should be strictly based on the Bible, especially since Van Helmont found everything Aristotle wrote as contrary to the Bible (as well as nature).

Indeed it was on these “straits” that Van Helmont, using the language of the sea, believed De Heer’s argument fell apart, driving and dashing “a certain Author, of the Fountains of the Spaw, against the Rock.” Indeed, so blasphemous did De Heer’s explanation seem, that Van Helmont felt forced to challenge him.

For although I shall dissemble any thing that is of Mans weakness in the same, yet Christian Piety in an honest man, doth not suffer publique Blasphemy to pass over un admonished of: The which Author therefore, I beseech to indulge my Liberty. 18

But he believed that de Heer’s interpretation of the Bible was flawed. For example, Van Helmont criticized De Heer’s claim that subterranean vapors/exhalations were the source of many springs. The trouble with this for Van Helmont was that there would be no way keep vapors/exhalations that came from earth separate from the vapors’ exhalations that came from the groundwater that originated from the seawater. Certainly De Heer could not deny vapors/exhalations from the earth and the inevitability of intermingling thus any explanation based on vapors/exhalations would inevitably go against the statement in the Ecclesiasticus of Jesus Syrach, “whereby he would have all Rivers (by consequence also Fountains) to proceed and issue from the Sea, and at last to finish their Courses into the Sea”. 19

Van Helmont had to acknowledge that nowhere did the Bible explicitly state how the waters of the sea actually became the water of rivers and fountains. 20 Thus he conjectured his own theory, but one he believed much more in line with Scripture than De Heer’s.

Water circulates between the sea and the deepest layers of earth. The latter is earth at its most pure, its ‘live and vital ground’, a uniform white sand (quellem) deep down under the surface, by contrast with the multi-coloured mineral gravel that is visible to us as ‘earth’. Here lies the source from which the sea and all the rivers, brooks, and fountains come and to which they eventually return. Water dwelling here does not obey the laws of hydrodynamics; it does not ‘know of above and below’, just as blood does not, as long as it courses through the vessels: once it has left their confines, blood will ‘obey the laws of places’, and so does water surging up from the depths of sand (quellem). 21

Beyond these differences of opinion about how to logically interpret the Bible, what really seemed to set Van Helmont off was when De Heer turned to Aristotle. In particular Van Helmont rejected Aristotle’s (and de Heer’s) theory that air might be transformed into water. Van Helmont’s hatred of Aristotle went far beyond the fact that Aristotle was a pagan. 22 Indeed Van Helmont had no problem using Plato to chastise Aristotle, finding Plato’s views to be compatible with a scriptural explanation.

Van Helmont criticized Aristotle on several grounds. Firstly, Van Helmont complained that Aristotle, even though he was a student of Plato, was ignorant of Plato’s statement in Phaedo that the four rivers of Paradise issued forth from the command of God. 23 Van Helmont finds it problematic that if springs are indeed formed the way Aristotle describes “only by a constriction of the Air”, why would they not have done so from the Creation?

Aristotle (he saith) would have all Fountains and Rivers to be bred of Air resolved into Water : He had not read, I believe, although he were Plato’s Schollar, that those four Rivers of Paradise, (in Phaedo) issued forth from the Command of God. Why I pray thee, if thou sayest, that great Rivers are even at this day also bred only by a constriction of the Air, have they not also (Phaedo being read) and Nature moreover, being a Virgin, issued from the same Constriction, forthwith after the Creation? And he who believed the World to be from Eternity, to have left Phaedo neglected, nor to have expected any condensing of Air; unless perhaps he doated before Goropius Becanus; That those four Rivers were nothing else, but the Ocean sending forth Rivers into the four Coasts of the World : in which Sense also, the Syrachian Preacher saith, That all Waters do come from the Sea, and again, that having passed their Course, they render themselves unto the Sea : which Words do thus found in the Schooles. 24

Indeed Van Helmont’s theory of the nature of subterranean waters shares so much in common with Phaedo that one wonder how much Van Helmont’s theory is more Platonic than scriptural. 25

Van Helmont rejected Aristotle’s four element theory outright. On scriptural grounds, Van Helmont believed only in two elements: air and water. And beyond that he gave primacy to water. 26 “In creation water emerges before the first day; it constitutes heaven., the very object of creation. The Hebrew heaven (schamajim) stands for ‘there is water’ (schom-majim)” 27 On scriptural grounds alone, Van Helmont totally rejected Aristotle’s (and de Heer’s) assertion that air could transmute into water.

Van Helmont believed that all earthly things including earth, rocks, metals, as well as organic matter with derived from water and ultimately reducible to water. 28 “Water, then, plays the part of base (matrix) and carrier to minerals and metals. It is the bearer of their semina; these are the units that contain ‘Nature, Essence, Existence, Gift, Knowledge, Duration, Appointment’, concentrated into a small space, still united and undispersed” 29 “Water moving in a ‘circle’ between sea and earth and back to sea serves to distribute the semina. These are stored in the entrails of the earth. They include in particular the semina of minerals and metals, and are appreciated as ‘reasons and gifts’, spiritual directives, that is, which are to receive bodily garments” directed by God 30

Experimental Grounds

Van Helmont believed that one did not have to take his anti-Aristotelian interpretation of primacy of water strictly on faith. For he believed experience also proved him right.

His most famous evidence was the willow tree experiment.

But I have learned by this handicraft-operation, that all Vegetables do immediately, and materially proceed out of the Element of Water only. For I took an Earthen Vessel, in which I put 200 pounds of Earth that had been dried in a Furnace, weighing five pounds; and at length, five years being finished, the Tree sprung from thence, did weigh 169 pounds, and about three ounces: But I moystened the Earthen Vessel with Rain-water, or distilled water (always when there was a need) and it was large, and implanted into the Earth and least the dust that flew about should be co-mingled with the Earth, I covered the lip of the mouth of the Vessel, with an Iron-plate with Tin, and easily passable with many wholes. At length, I again dried the Earth of the Vessel, and there were found the same 200 pounds, wanting about two ounces. Therefore 164 pounds of Wood, Barks, and Roots, arose out of water onely. 31

But even before the willow tree experiment, in the Supplementum Van Helmont was providing experimental evidence to refute the assertion that air can transmute into water.

At length take thou also this handicraft Experiment: Air may be by force pressed together in an Iron-pipe of one Ell long, that it can scarce fill up the space of five fingers; the which afterwards, in its enlargement, casts out a Bullet like a Hand-gun, it being driven with fire: which thing verily should not happen, if Air being pressed together, could through the coldness of the Iron, be made Water. 32

De Heer’s Response

De Heer immediately responded in print with a Deplementum to Van Helmont’s Supplementum, subtitled Vindiciae pro sua Spadacrene. 33 According to De Heer, the Prince of Liége order him to refute Van Helmont. 34 But vicious tone of the attack — at one point referring to Van Helmont as os inferni as mentioned above — seems to have been all de Heer. 35

De Heer certainly had to respond to Van Helmont’s extended direct criticism of his theory of the origin of springs. In order to refute Van Helmont’s point that air could not be transmuted into water, De Heer that such a transmutation did happen and it did not even take centuries; it could happen in the course of just a few months. As proof he points to a perpetual motion machine that an astute mathematician had invented to determine which part of a house was colder or warmer. The machine ingeniously contained a deep red water prepared by chemical means (auf chemischem Wege) with spirit of vitriol (Vitriolgeist) and a red dye (Rosentinktur), fully enclosed with air.

But what happened? Both in my home and at various other places, the precious water is gone and gone to air, because there was not another exit. All of Liege, the illustrious prince, the whole court, countless visitors to Spa have kept those glasses in hit hands and seen the transformation of water have painful regrets in air, for at that moment it was made with the wonders of mathematics. What do you think? Here was water, and now it is gone, that has either a transformation of what is, in what is not, naturally, paths taken place or the water has been turned into air, say to me, all you alone deny. Do you think that your arguments are childish prattle, that can refute the youngest pupil of Aristotle? 36

De Heer does not inform us who this astute mathematician was nor does he give us a description of the apparatus, but Van Helmont seems to have believed that this was an apparatus which he himself had built and which De Heer had totally misused toward the wrong conclusion. He did this in an essay “De Aere” which was not published until after his death but which seems very much written (at least in part) in the heat of the moment, with Van Helmont descending to the kind of ad hominems that De Heer had employed against him. 37

To demonstrate that air could NOT be transformed into water no matter what the pressure or temperature, Van Helmont designed a “mathematical demonstration” (demonstratio mathematica) or, what we might call a formal proof, employing a piece of apparatus called a thermoscope, “to falsify the thesis according to which water and air can be transformed into one another”. 38

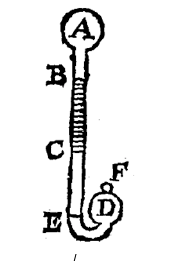

Figure 1 Diagram of Van Helmont’s Thermoscope

Two spheres A and D are connected to each other by BCE. Both spheres are filled with air. The pipe BC is filled with vitriol which was coloured red by the steeping of roses. It is essential that the two spheres are perfectly closed “perfectissime clausa” 39

Van Helmont established by observation that without the opening in F, the liquor in BC cannot be moved from its place by heating the air in A. (See Figure 1.) Van Helmont points to the great practical difficulty of the experiment:

The preparation of the demonstration. It is very great, because the air suffers enlarging, and the heaping together or straightning, according to the qualities of the heat and cold, and because the just extension of quantity is not had in the air, unless when it is temperate. 40

When heating the air in A no extra water was produced. Van Helmont explained this by assuming that the air in the upper part of the vessel thickened as it tried to expand (“Aër (…) accrescit per augmentum dimensionum, & ideo occupat plus loci, quam antea” 41). The amount of fluid remains the same.

Next, Van Helmont proceeded to show that the water cannot dry up (“exsiccare”) or be exhaled (“exhalare”) by heating, if A and D are kept carefully shut. Since no extra water was produced when heating the air contained in A, the thesis that air can be transformed into water is untenable, according to Van Helmont. Similarly, since no water disappeared when heating the vessel, the thesis that water can be transformed into air (“quod liquor sit mutatus in aëris”) is untenable. 42

In Van Helmont’s mind this simple demonstration completely refuted de Heer’s claim air can be transmuted into water. “Van Helmont stressed that van Heers faulty interpretation was due to his ignorance of mathematics:

But Heer boasted amongst Idiots, that he had sometimes been a Professour (sic) of the Mathematicks at Padua. Wherefore I would demonstrate in paper, his every way ignorance of Mathematics. 43

Van Helmont furtherwent after De Heer’s misuse of his apparatus:

Although I have plainly shewn in the presence of many, that Heer, in his Apologie or defence against my little Book concerning the Fountains of the Spaw, had impertinently made use of my Instrument: yet he hath not been wanting to mingle me with his stupidities and sottishnesses. For he saith, that I would set forth a continual motion. Neither indeed hath he known, that in that, he hath contradicted himself. For the motion ceaseth in the Instrument, after that the water hath ascended or descended, according to the temperament of the air encompassing it. For neither can that motion be any more called perpetual, than the vane of a Temple appointed for the changing of the winds. Therefore Heer hath discovered, that he knowes not what perpetual motion is. For I had divulged my Instrument, that according to my Doctrine of the Fountains of the Spaw, I might prove that the air did sustain its common rarefaction or making thin, and compression or co-thickning, without the changing of its Element. 44

In addition, Van Helmont asserted that the apparatus proved that De Heer was also wrong in claiming that the spirits escaped from well-stoppered bottles of Sauveniere water, something that Van Helmont had not addressed in Supplementum.

For Heer saith, that the Spirit of Vitriol hath pierced the substance of Glasse; which thing, none will grant, who have known that far more subtile Liquors are preserved even in the fire. Neither hath it helped him, that I had affirmed to him, that Clavius in the Colledge of the Romane Society, had shut up water in a Glasse of this Figure, 60 years before, whereof not the least drop had perished. 45

Curiously, although Van Helmont suggests he had been building this thermoscope before De Heer’s Deplementum (which was written immediately after the appearance of Van Helmont’s Supplementum), Van Helmont makes no mention of the thermoscope in Supplementum. Since Van Helmont was drawing upon any argument he could to refute De Heer’s views — and indeed brought up the iron elbow experiment — why would Van Helmont not bring up the thermoscope. Unless, of course, he had not begun to experiment with the thermoscope yet and De Heer actually was writing about somebody else’s apparatus.

Whether De Heer had truly ripped off Van Helmont’s apparatus or was simply employing a similar kind of apparatus built by someone else is still up in the air. De Heer never described the glass. But the kind of device that Van Helmont described, as Andrea Borelli has noted, was “nothing other than a simplified version” of the kind of “thermometer” that Cornelius Drebbel (ca. 1572-1633) of Alkmaar in the Netherlands had invented by the first decade of the 17th century and which apparently were being sold all over northern Europe as “perpetuum mobile” by the 1620s. 46

Spa Waters Not Sour?

If De Heer’s misuse and misunderstanding of his apparatus was Van Helmont’s main peeve, De Heer’s chief argument with Van Helmont was his denial that Spa waters were acides. Indeed, the only mention that Van Helmont rates in later editions of Spadacrene is a beratement for being the only author to make such a foolish claim. 47

Actually it is not totally clear what De Heer is referring to with this claim because no where in the published work of Van Helmont does he actually come out and deny that Spa waters are acides. Indeed, Chrouet, who brought out a new edition of De Heer’s Les Fontaines de Spa in the 1739 (and who was quite sympathetic to De Heer), claimed he was not certain what De Heer meant by this. 48

What most likely De Heer was on about was Van Helmont’s claim that NO fountain, including Spa waters, had a truly sour taste. Surely this would have seemed ludicrous to De Heer as well as every writer on sour waters going back to Aristotle who claimed that certain waters tasted sour.

However, Van Helmont was not denying the existence of acidi fontes. Indeed, he followed Paracelsus in claiming marvelous virtues for such waters as the fountain in “Veltin [sic] a little Village of Helvetia” (i.e., the St. Mauritz spring) that Paracelsus celebrated in his Book of Tartarous Diseases. Van Helmont went so far as to claim that acidi fontes “do so most nearly imitate that universal Medicine, Moly Homericum, to wit, by defending of health, and propagating of the vital Powers, that they have seemed to have ascended as it were unto the top of Medicine”. Furthermore, contrary to Paracelsus and undoubtedly to the dismay of Spa supporters, Van Helmont asserted that such acidi fontes were not actually that rare. Indeed he believed there were many “in the highest rocks, far from the dregs, and among rocky stones and sand” where these waters arise and that truly the Danube, Rhein, Rhone, Sana, Po, etc. arise in their first spring from such fountains. 49

But Van Helmont does not believe these acidi fontes actually taste sour. Indeed, he finds they have a rather insipid taste. Still he does not reject calling these waters acidi fontes and indeed calls waters like Spa acidi fontes because medicinally the Spa-like waters and sour substances have similar medicinal virtues, although acidi fontes were superior because they contain the seed of an esurine salt (semen salis esurini) which, although it is as yet free from the unfolding of savours or any kind of co-mixture, Van Helmont still calls acidum because it is medicinally sharp and “cleanseth away, and consumeth altogether every Humour which is not Vital, and which is Tartarous”. 50 By sal esurinum, Van Helmont thus seems clearly to be drawing on Paracelsus’ acetosa esurine as the key actor in acidi fontes. Indeed Van Helmont writes about sal esurinum as if he had not invented the term; it was the name that others had come to be used. He notes that sal esurinum was also known by the names sal acetosum and sal acidum.

Medicinally, Van Helmont, like Paracelsus, emphasized the salt’s ability to “cleanseth away, and consumeth altogether every Humour which is not Vital, and which is Tartarous,” to the point of reiterating Paracelsus’s story about the ostrich’s ability to digest all metals. 51 Although Van Helmont does not specifically mention the ability of this acid salt to dissolve bladder and other urinary calculi like Paracelsus, it seems a logical extension to assume that Van Helmont thought like Paracelsus on this matter since Van Helmont does not explicitly say anything to the contrary.

Van Helmont’s sal esurinum acted in many ways like Paracelsus’s acetosa esurine. Both could be found naturally in fountain waters and both could also be prepared artificially (Van Helmont’s oleum e vitriolo, Paracelsus’ acetosum vitriolatum). But Van Helmont dismisses claims that the oil of vitriol has anything to do with acidi fontes. He claims that nature does not produce an oil of vitriol. He notes that “nought but the extream torture of the Fires, doth allure forth a most sharpe Oyl out of Vitriol.” From that assumption, those who focus on vitriol suppose Spa-like fountains “wax sharp” because “such an Heat in the Earth doth stir up the sharp Spirits of Vitriol, unto the Superficies of the Earth, which being there constrained by Cold, and changed into a sharp Matter, are co-mixed with the neighbouring fountain.” But Van Helmont suggests there are two major problems with this explanation. First he notes “there is no such voluntary Distillation in the Universe,” meaning nowhere in nature is there the kind of intense fire one artificially uses to prepare oil of vitrol, so there is no oil of vitriol outside the alchemist’s laboratory. Secondly, and more importantly, Van Helmont notes that Spa waters do not act like waters that have been commingled with “the Spirits of Vitriol.” Spa waters lose their sharpness in time and become “tinged with a ruddie colour,” but waters with spirits of vitriol do not. 52

Like Paracelsus, Van Helmont also emphasizes the connection between this sal/acestosa esurinum, metals, and vitriol. Van Helmont referred to sal esurinum as an “hermaphroditical salt of metals”, capable of converting all metals whatsoever into that metal’s associated vitriol. 53

However, there are significant differences too. Van Helmont’s sal esurinum is volatile. Van Helmont also links sal esurinum to sulfur. Van Helmont claims “that the sharp hungry Salt of Fountaines born in the Bowels of the Earth, is the Salt of any Sulphur embryonated or not perfected : Yet that it is by so much the more noble than an Artificial Salt fetcht out of Sulphur, by how much it is nearer to its first Being…the hungry Salts of Sulphur do most far differ from the property of Sulphur”. 54 Van Helmont says this explains that it due to “the activity of an hungry Salt” that the water smelled like sulfur even though there was no body of sulfur present. 55

As we have noted in previous chapters, sulfur was regularly associated with Spa waters going back to Bruhezen and Fuchs through de Heer. Pidoux had noted a sulfur smell about the waters and proposed a strong association between sulfur and vitriol, indeed that vitriol could be prepared from sulfur.

Redefining Spa Waters

Van Helmont poked fun at the endless list of ingredients that earlier writers had claimed to find on distilling Spa waters. Simply put, these chemists were seeing too many things that just were not there based on inadequate chemical analysis, reporting long lists of phantom elements. Van Helmont does not single out De Heer’s analysis, but simply lumps him with all the other writers who have completely overblown the mineral/metal contents of Spa waters.

But in respect of the thing contained in the Water of the Spaw, they [Writers] far disagree from us : For indeed they affirm, that Vitriol is in the Water of the Spaw, and that Calchitis or red Vitriol, Mysy, Sory, Melantera or Blacking, Salt, Nitre (that Nitre I say, hath been found to be in them, by the examination of Distilling, which elsewhere they never saw, because they testifie it is that which since the Age of Hippocrates, had failed from thence) Bitumen, or a liquid Amber, the pit Coal, Alume, Bole, Oker, Red-lead, the Mother of Iron, the Vein of Iron, Iron, Ærugo or Verdigrease, burnt Chalcanthum, Burnt Alume, also the Flour of Brass and Sulphur, have therein discovered themselves : These things I say, we read to be attributed by Authors, unto to the Fountains of the Spaw, under their Mistris Uncertaint; and so they doubting unto what Captain they may commit so great an Army, do conclude, that there are some Fountains, in which thou mayest most difficulty discern an eminent Subterraneous Matter. 56

When Van Helmont distilled Spa waters, instead of a litany of minerals and metals, all he found was common aqua fontana (“fountain water”) and vitriolum ferri (“vitriol of iron”), which he claims no one had yet identified in the waters. 57

However beholden to Paracelsus, Van Helmont in Supplementum would totally redefine the way Spa waters were perceived.

Hitherto the Opinion of others led me aside. I will confess my Blindness. I at sometime seriously distilled Savenirius, and Pouhontius; and indeed, I found not so great a Catalogue of Minerals, yea not anything in them, besides Fountain water, and the Vitriol of Iron, by other Writers before me neglected : But the Vitriol of Mars consisteth of the hungry Salt of embryonated Sulphur and of the Vein of Iron (not of Iron) which Vein, the hungry Salt being as yet volatile, hath by licking, corroded. 58

Van Helmont proceeds to flesh out the implications of this power-packed statement in the remaining pages of the Supplementum, demonstrating how the theory explains many phenomena associated with Spa waters. But to understand the significance of the statement as well as the unresolved problems associated with Van Helmont’s early approach to Spa waters, we need to break down his explanation into smaller, more digestible chunks.

Vena ferri

“The vein of iron” is one of the substances that Van Helmont claims earlier analysts had identified in Spa waters, but it is not exactly clear what he meant by the term.

He explicitly states “the vein of iron” is not the same as “iron, or the fragments of iron”, that the vein comprises “those subtile Parts, which the Furnace filched away in time of Fusion” which gives it greater medicinal virtue than iron. He also mentions “the dark Body of the Vein of Iron.” 59

Although Van Helmont seeks to distance “the vein of iron” from iron, some other details do not suggest the two were that different. For example, in explaining why Spa waters turn feces black, Van Helmont mentions nothing about the vein of iron, only iron, just like De Heer.

Stomoma therefore, that is, Steel or Iron Administred in Powder, being drunk down; as soon as may be, that hurtful Salt (which hearkens not to the commands of purging things) runs headlong unto the Iron, and adheres unto it, that it may dissolve that, and display its own Faculty: and so is Coagulated nigh that, and together with the Iron, goes forth. But if the Iron or Steel be drunk, being dissolved in a sharp Liquour, yet not hostile unto us (to wit the Spaw waters) Nature, the same liquours being wasted, and more inwardly admitted within, presently separates the Iron (because it is unapt for nourishment) from that which was co-mixed with it, and sends it forth thorow the Bowels: As may be seen in the blackness of the dungs of the Fountains of the Spaw.

In which Sequestration of the Iron, there is straightway made a Con-flux of Mineral Salts, no otherwise than as Silver dissolved in Chrysulca or Aqua Fortis, doth flie unto applyed Brasse, and dissolved Brasse, unto Iron: The received Iron therefore, freeth from obstruction, and openeth by accident, to wit, the vanquished obstructing matter being taken away with it: yet not that it therefore ceaseth by it self, to be constrictive. 60

The other medicinal virtues that Van Helmont identifies for Spa waters are also those typically associated with plain old iron.

That therefore first of all, doth manifestly binde, and therefore it strengthens the Stomach, and any of its neighbouring parts. In loose therefore, and dissolute Diseases, the Waters of the Spaw do agree or are serviceable, to wit in those of the Lientery Flux, Cæliacke Passion, and Dysentery or bloody Flux, &c. 61

Van Helmont also describes how the vein of iron undergoes a transformation, suddenly appearing out of clear water where it had before been invisible.

At length, it is also easie to be seen, why the Waters about the end of their activity (for that speediness of solution doth continue a longer or shorter time, in diverse Fountains) do loose their Sharpness, and why the Vein being before transparent, doth then appear ruddy. 62

Not only does the vein of iron suddenly appear but there also appears to be a color change because here the vein appear ruddy whereas before it was described as a “dark body”. [One presumes that Van Helmont would not describe rusa as a “dark” color.]

The sudden appearance of this ruddy sediment strongly suggests that Van Helmont is describing the same substance that many Fuchs had decades earlier had called rubrica or mater ferri. However, Van Helmont does not make any such connection.

Spirit in the Water

As we have seen, just because Van Helmont rejected De Heer’s claim that spirits could escape from a well-stoppered bottle, he did not reject spirits in the water. Indeed, spirits play a very important role in Van Helmont’s analysis of Spa waters.

The Salt I say, as long as it is volatile, that is, apt by being pressed by the Fire, to fly away, is reckoned among Spirits. But Bodies do not corrode Bodies, as such; neither do fixed things act on, or into each other; but only as one of them is volatile, that is, a Spirit, whether it be grown together, or liquid. 63

He sees “the hungry Salt of embryonated Sulphur” as volatile, one of the spirits. Furthermore, this spirit is what we might describe today as “chemically active”. Indeed, he asserts that only spirits are chemically active.

He also acknowledges, as others have, that volatile substances have a tendency to fy away, especially when distilled. He equates volatile substances with spirits. He also suggests that Spa waters are lighter due to the presence of the spirit acting on the vein and the lightness of Spa waters was a commonplace observation. “The presence therefore of the Spirit acting into the Vein, enlargeth the Pores in the Water, and works up the Water of the Fountain into a lighter weight”. 64

Exhalationes sylvestres

Furthermore, Van Helmont here in Supplementum refers to exhalations. He states that such exhalations occur in all solutione as can be seen in the activity of aqua fortis, distilled vinegar, etc. What Van Helmont seems to have in mind here are the bubbles that often form when acids dissolve various substances like metals, carbonates, etc. With regard to Spa waters, the essurine salt in dissolving the vein of iron stirs up these exhalations. He calls these exhalations “wild”.

In the next place, in all solution (as may be seen in the activity of Aqua Fortis, distilled Vinegar, &c.) Some Exhalations are stirred up, being before at quiet, which as they are wild ones, they do not again obey coagulation; therefore the Waters do of necessity fly away, or being restrained, do burst the Vessels. 65

Here Van Helmont seems to distinguish between spirits and exhalations in that spirits are inherently volatile and thus always apt to fly away especially when distilled but are capable of coagulation, whereas exhalations are only stirred up by some kind of dissolution and are incapable of coagulation. If not restrained, he claims the waters of necessity fly away. But if restrained, the waters burst the bottles.

It is hard to know how far Van Helmont wants to take the analogy about “all solutions” to Spa waters. Does he mean to imply that any attempt to bottle Spa waters will lead to burst bottles if well-stoppered? He certainly does not raise that point when he criticizes De Heer for claim that spirits escape from bottles. In the 17th century there will complaints about burst bottles from some Spa-like waters (see later chapters) but there had not been any records of such complaints in writing by the time Van Helmont wrote.

It is further to be noted, that even as in Wines, and unripe Oyl of Olives, there is a fermental boyling up; So the Action of the hungry Salt it self, is made: And not only upon the Vein, while it gnaws and passeth thorow the same; but also it operates for some time, upon the same, being snatched away with it: Pouhontius I say, far longer than Savenirius, &c. until that the Activities of the Spirits being worn out or exhausted, as well the Agent, as the Patient, the thing dissolving I say, like as also the thing to be dissolved, do decay or faile in the same endeavour. 66

By “fermental boyling up” it seems Van Helmont means the bubbles which he thus attributes to the exhalations rather than the spirit.

The model also explains why the water appears perfectly clear even with the physical presence of the dark vein of iron in the water. Van Helmont explains that as long as the hungry salt is acting on the vein of iron, the vein of iron is invisible, suspended in the water.

From hence therefore, a reason plainly appeareth, why the Waters of the Spaw, in so great a clearness or perspicuity, do hide in them the dark Body of the Vein of Iron. 67

Van Helmont leaves unclear exactly how this action could hide ALL the vein of iron. If the analogy is to the dissolution of a solid body in aqua fortis or distilled vinegar, the solid body is quite visible until it is totally dissolved.

Van Helmont also suggests these exhalations have a sulphurous smell although this seems problematic

Next, why in the activity of an hungry Salt, they do cast a smell of Sulphur, notwithstanding the corporal Sulphur be absent. 68

As we have seen in the previous two chapters, there was a long tradition going back to Fuchs of reporting fumes of sulphur in Spa waters. The presumption seems to be that since the smell of sulphur requires the “activity” of the hungry salt, that the sulphurous smell is in the exhalations rather than any escaping spirit which as far as we know is tasteless and presumably odorless. But Van Helmont does not explain why the exhalations should have a sulphurous smell.

“Their Natural or Proper Simplicitty”

But, over the course of the action, some of the volatile salt escapes the water and other weakened and coagulated. When all of the hungry salt has either escaped or weakened and coagulated, the imbibed vein of iron appears and settles to the bottom and the water become no different than common water.

At length, it is also easie to be seen, why the Waters about the end of their activity (for that speediness of solution doth continue a longer or shorter time, in diverse Fountains) do loose their Sharpnesse, and why the Vein being before transparent, doth then appear ruddy.

To wit, the Spirits being now partly chased away, or the same being weakened, and coagulated at the end of Activity, the imbibed Vein settles, and is manifested, which before had remained hidden; the Waters in the meantime, recovering their natural or proper Simplicitty. 69

In explaining so nicely why Spa waters lose their medicinal virtue and return to simple water, Van Helmont was following right in line with French writers like Pigray and Pidoux. In the process of corroding and dissolving the vein of iron, some of the hungry salt escapes and the rest loses its volatility and coagulates. But for Pidoux such an explanation worked because the active ingredients eventually escape the water and distillation reveals nothing but common water. Van Helmont offers no such escape.

Newman and Principe suggest that this seems to be an example of the phenomenon that Van Helmont calls “exantlation” (from the Greek word exantlein, “to pump out”.

Exantlation refers primarily to the loss of activity that corrosives such as acids suffer when they act on another substance. For example, a given quantity of nitric acid can dissolve only a certain amount of silver, after which time it is used up and the residual fluid is no longer corrosive. But Van Helmont did not think of the corrosives as being neutralized by going into combination with some other substance; instead, they gradually became enfeebled in the same way that an animal might become tired after exerting itself (although the corrosive, unlike an animal, would not become reinvigorated by repose). Now what was it, we might ask, that led Van Helmont to this counterintuitive result, other than his general tendency to favor the action of internal principles of activity (such as semina) over external efficient causes? In part he was driven by his rejection of a prevailing chymical theory that acids acted merely be grinding substances into bits so small that they were no longer visible in a solution. He points out that this theory does not account for the lessening of the acid’s strength, nor does it explain why some acids ‘congeal’ in the very act of dissolving another substance. But we are still left with the obvious question: why did Van Helmont create the theory of exantlation rather than simply arguing that the particles of acid went into combination with those of the solute? After all, he had a workable corpuscular theory, which he employed to debunk the belief that vitriol springs actually transmuted iron into copper. 70

Van Helmont believes that Spa waters are only beneficial as long as the hungry salt is acting on the vein of iron. He does not describe the ruddy vein of iron that settles to the bottom as particularly useful medicinally.

For Van Helmont, it was clear why the Sauvenir lost its virtue more easily because it had “less of the Vein, and hungry Salt; and therefore it sooner finisheth the Action of the hungry Salt and Vein, and the Medicinal water sooner dyeth: And for the same Cause, it must easily passeth thorow the Stomack, is sooner concocted, and doth penetrate”. 71

Martis vitriolum/Vitriolum ferri

Van Helmont asserts that martis vitriolum/vitriolum ferri in Spa waters forms through the interaction of the sal esurinum and the vena ferri.

But the Vitriol of Mars consisteth of the hungry Salt of embryonated Sulphur and of the Vein of Iron (not of Iron) which Vein, the hungry Salt being as yet volatile, hath by licking, corroded.

In which Act of corroding, there is made a certain kind of Dissolution of the Vein it self, and a coagulation or fixation of the volatile Salt… 72

But besides that also is afterwards to be noted, that how much of the Spirits hath compleated the solution of the Body, so much also it hath assumed a corporality in the solved Body. 73

The implication is that as the hungry salt dissolves the vein of iron, it coagulates and they join together to form that Van Helmont calls martis vitriolum. He seems to intend by iron vitriol some kind of physical union between the two substances. As the hungry salt completes the corrosion of the vein of iron, the hungry salt assumes a physical presence in the dissolved vein of iron, i.e., the hungry salt unites materially with dissolved vein of iron. This then would be the substance he claims to have identified in the waters by distillation.

Although Van Helmont does not make the link explicit, the only way to make sense of is description of Spa waters is to assume that martis vitriolum/vitriolum ferri (which he claims is the only substance left after distillation) is one and the same as the ruddy imbibed vein of iron (which he claims is the only substance left in the water when it is left to its own).

Unfortunately, Van Helmont’s use of the terms martis vitriolum and vitriolum ferri has caused a lot of confusion over the centuries, with modern scholars assuming he must have meant some kind of iron salt (e.g., ferrous bicarbonate, ferrous sulfate). 74 But there is no inkling of such a meaning in Van Helmont’s work.

Indeed in the early 17th century, other scholars were working toward starting to conceive of a substance they called iron vitriol which was akin to the greenish glassy substance we call ferrous sulfate heptahydrate. Although there was still a lot of confusion over, say, whether green vitriol was copper vitriol or iron vitriol, the general consensus in the early 17th century was that vitriols by definition were glassy substances. Only Van Helmont opted for a completely off-the-wall definition of martis vitriolum as a substance that almost everybody else, following Fuchs, was calling rubrica.

We have already explored the early ideas about vitriol/chalcanthum/atramentum of Paracelsus, Agricola, Fallopio, et al. Beginning with Paracelsus, there was a growing sense that vitriol was not strictly something associated with copper, that each metal had its own vitriol. Furthermore, going back to Agricola, writers were consistently describing three basic colors of vitriol: green, blue, and white. But there was no consensus at the time Van Helmont was writing about how to prepare the vitriols of these different metals or distinguish between them based on color or any other feature.

Libavius summarizing the literature on martis vitriolum in 1615 mentioned in particular three writers: Turquet de Mayerne, Raphael Eglin, and Oswald Croll.

Turquet de Mayerne (1573-1654 or 1655) was the favorite physician of Henri IV but such a privileged position was not enough to protect a follower of Paracelsus from the wrath of the medical establishment at the turn of the 17th century. The College of Physicians of Paris in 1603 expelled Mayerne from its ranks for the nominal offence of having “published a defence of his friend, Quercetanus, who prescribed mercurial and antimonial medicines.” The College condemned Mayerne’s Apologia (1603) as

an infamous libel, stuffed with lying reproaches and impudent calumnies, which could not have proceeded from any but an unlearned, impudent, drunken, mad fellow : And do judge the said Turquet to be unworthy to practise physick in any place because of his rashness, impudence, and ignorance of true physick : But do exhort all physicians which practise Physick in any nations or places whatsoever that they will drive the said Turquet and such like monsters of men and opinions out of their company and coasts ; and that they will constantly continue in the doctrine of Hippocrates and Galen. Moreover, they forbid all men that are of the Society of the Physicians of Paris, that they do not admit a consultation with Turquet or such like person. Whosoever shall presume to act contrary shall be deprived of all honours, emoluments, and privileges of the University and be expunged out of the regent Physicians. 75

In his Apologia (1603), according to a summary in Libavius, also wrote addressed the preparation of green vitriol. “Turquet writes, nearly all iron to be changed into vitriol. You mix spirit of vitriol with common water. Into the mixture you throw squama (scales) of iron, or fragments of iron in order to be corroded. You distill drawn off fluid [humor decapulo] to the right thickness, which is required in so great diluted. You repeat to be congealed so that crystals should be produced according to art. Green chalcanthum will escape which easily transmutes into copper.” 76

Another early writer to mention green vitriol was Raphael Eglin (1559-1622), a Swiss theologian, alchemist, and Paracelsian physician. Eglin obtained a theological lectureship at Marburg University in 1606 where he came into contact with Oswald Croll. 77

Heliophilus makes use of similar art. You extinguish thin sheets of steel made white hot in cold water to so many times as to harden, and would be able to be torn into pieces with no trouble. You shatter the equal of a nail or of scale. You take hold of one part of the sour spirit [spiritus acidus] out of sulfur, & twice as much of fountain [water]. It would become creams. Into this you throw dry irony nails in thick glass cucurbita, which you bring into ashes, and you cook with excited fire, while the water should boil gently for six hours in a blocked up vessel. While through itself shall be cooled, you will discover on the surface in the cucurbita, shining green vitriol, because by this art should be transmuted into copper, or out of iron or steel it should bring forth copper, you should be able to see according to Elias artista. 78

However, contrary to Libavius, it is not clear that either Mayerne or Eglin understood what they had prepared as iron vitriol. They only refer to green vitriol (Mayerne’s chalcanthum viride and Eglin’s vitriolum viride). Furthermore they both emphasize how easy it is to transmute this green vitriol into copper. They obviously were thinking in terms of Paracelsus’ description of vitriol but did not recognize that only the blue copper vitriol could easily “transmute” into copper by the addition of iron. Neither Mayerne nor Eglin mentions blue vitriol. Indeed, as we will see below, Jean Beguin later criticized Eglin for ignorantly denying that he had produced a salt of iron.

The first to truly distinguish between the iron vitriol (vitriolum ferri) as green (viride) and copper vitriol (vitriolum cupri) as blue (caeruleum), from both of which the spirit and oil of vitriol can be prepared, seems to have been Oswald Croll (c. 1563-1609), alchemist and professor of medicine at the University of Marburg, in his principal work Basilica Chymica (1609). 79 Partington asserts that Basilica Chymica “probably was the main source from which a knowledge of Paracelsan medicines and teachings became known”. The book went through numerous Latin editions in the 17th century and was translated into French, English and German. 80 As Libavius summarized Croll’s description of vitriol,

Crollius teaches vitriol of Mars and Venus is made out of sulfur without being corroded. Fragments of small pieces of Mars, or the equal of the twenty-fourth part of coins of Venus with powder of sulfur. in a large clay crucible equipped are arranged alternately become accustomed to be made in cementing. A large crucible surrounded by a circular fire thus at first would not be touched, but little by little the neighboring growth would be added during the hour. The sulfur set on fire will burn up the thin sheets as they turn black. Whereas by means of themselves, they will have grown cold, extracted and crushed you throw into the jar covered with side walls into the side, & with adjacent live coals you stir repeatedly with iron spoon in iron and copper [spoon] in copper, in order to be made in the calcination of vitriol becomes accustomed to lest they liquefy and the chalcanthum be destroyed. This therefore is made as sulfur which thus far remains burns up, & is dispersed. As it begins to adhere to the spoon you remove from the fire you add one-eighth of a pound of powder of sulfur, & you restore into the pot strewn as earlier and with live coals place under you stir over the slow fire for a quarter of an hour. You increase gradually the fire, to the highest the jar as if would make white hot. The copper is the habit to become soft & iron to cling to where it is stirred. As soon as it is grown cold the worn-out calx extracted and dried & by means of a sieve transported you mix with sulfur a second time, & in the same manner the art of calcining. And you repeat it six times, or yet again seven. Finally you put the calx into a wooden dish reduced into a finished finely ground powder, & you pour on boiling hot water which vitriol from the loosened calx will take up blue tinted out of copper but green out of steel or iron. You boil the filtered water all the way to the consistence of thick dissolved, while just as it acquires a crust, or appears a sign of formation into crystals. Put into a cold place, and collect hardened stones, which out of copper they will be blue, out of iron green, around which the sulfur of copper & iron remains which you repeat separately. Because moreover not all the calx is dissolved in the water, whatsoever stays behind, redried again by means of sulfur as the art of calcining done before, and extract or loosen by means of water while all should be exhausted vitriol. 81

Since Libavius identified in 1615 the green vitriol preparations of Mayerne and Eglin under the heading of vitriolum martis, he like Croll seems to suggest that vitriolum martis is green although he does not clearly characterize copper vitriol as blue. 82 But the issue hardly seemed resolved.

It would seem that with such a clear distinction between the blue vitriol of copper and the green vitriol of iron that confusion between the two would have come to an end. However, that was not to be the case. For example, Jean Beguin (1550-1620) in his highly popular Tyrocinium Chymicum (“Chemistry for Beginners”) gives a confusing account of vitriol. 83 In his recipe for the “salt or vitriol of iron” Beguin copies Eglin’s recipe for green vitriol but, as already mentioned, Beguin criticizes Eglin for ignorantly denying that this is a salt of iron. 84 However, Beguin does not clearly distinguish between the “salt or vitriol of iron” (for which he does not identify a color) and the “salt or vitriol of copper” (which he describes alternately as green and blue). 85

Furthermore, Beguin has an interesting passage in which it is clear the associated metal plays little to no role in the color of the vitriol.

Il y a trois especes de vitriol, le blanc, le vert, & le bleu, participans de la nature du sel, de l’alum, & du souphre, selon le plus & le moins. Car le blanc tient plus de l’alum, le vert plus du sel, & le bleu plus du soulfre. Tous neantmoins sont composez de parties aqueuse, terrestre, & moyenne entre ces deux: laquelle moyenne partie, selon Riplaeus en sa pupille d’Alchimie, ne peut estre separee des autres deux extremes, que par le moyen du Mercure, qui selon Geber retient ce qui est de sa nature, & reiette ce qui n’en est pas. Cette substance moyenne & diaphane est par sublimation exaltee à vne blancheur de neige, qui contient occultement vne substance sulfuree rouge comme escarlate. Et pource est dit en la Turbe. Les Philosophes se sont esmerueillez de ce qu’vne si grande rougeue estoit cachee dans vne si grande blancheur. Et de ce soulfre parle Geberau vingt-huictiesme chapitre de sa somme disant par le Dieu tres haut, il illumine & rectifie tout corps : car il est alum & teinture. C’est ceste eau de vie, & ceste eau seche, qui ne moüille point. C’est ceste equ congelee & ce sel animé, duquel parlant Raymond Lulle apre Alphidus, dit que le sel n’est que feu, & le feu n’est que soulfre, & le soulfre n’est qu’argent vif, reduict en celle pretieuse & incorruptible substance, que nous appellons nostre Pierre. Et vn certain faisant allusion sur les lettres de ce mot. Vitriolum a dit. Visitabis Interiora Terrae, Rectificando Inuenies Occultum Lapidem Veram Medicinam. 86

The physician Angelus Sala (1576-1637) reprinted Croll’s description of the preparation of vitriols of copper and iron in his 1617 edition of Anatomia Vitrioli, originally published in 1609. 87 The discovery of Croll’s writing on the subject seems to have had a great influence on Sala since in the earlier editions he had not even dealt with the issue of copper versus iron vitriol but in the 1617 edition he turned his attention fully to the subject. Sala also identified the three basic colors (blue, green, white) of vitriol. Unfortunately Sala neither in Anatomia Vitrioli nor in a later work De Natura Proprietate, et usu, Spiritus Vitrioli (1625) clearly associated either iron vitriol or copper vitriol with a particular color. Nevertheless, Sala went to greater lengths than any previous writer to explore the nature of vitriol.

In a nutshell, Sala described the composition of vitriol.

It [vitriol] is body prepared in the deepest entrails of the earth, out of a sulphurous spirit, water & mineral of copper, iron, or both mixed together. From the spirit of sulfur it acquires its acrimony, & caustic faculty : from water, clarity, & fluidity : & from mineral (whether copper, or iron, or both) color & metallic taste. To discover the truth by me, I will persuade by these two irresistible examples: the first is, when vitriol is dismembered & anatomized (as so I will call) by the fire, it is separated into these three particular substances, clearly water, spirit of sulfur, & mineral : the second is, because through the mean/midst and conjunction of the three preceding things by a certain artificial manner we would be able to be made vitriol, with respect to which it will maintain the same form, color, clarity, glassy brilliance, weight, odor, taste, and other qualities ; & in accordance with test the fire will bring out in short the colors from itself, and will give in short the same effects ; which in fresh natural vitriol out of mineral taken we commonly discover. 88

Next he detailed how exactly vitriol was prepared in the earth.

Therefore these two , simultaneously will have to be combining in its own vessels, they not only have use and are required according to the conjunction of minerals; & in truth the same occasion serve the interests by two other uses : the first is because how many bubbling springs of waters, or what kind of hot baths would bring out by diverse places one may see : second, because they prepare a certain menstruum or solvent (as called) suitable to vitriol will be produced. To know indeed we must, sulfur, after by natural fire, in said concavities of the earth are burned , to emit out of its body a certain spirit (spiritus) or if you will a vapor (vapor) exceedingly sharp (acer), & corrosive (corrosium), which into sunk (cadens) water on all sides (circumcirca) has been discovered (for instance in all deep hollow places of the earth generally water is in the habit to be discovered) those equally sour (acidus) and corrosive renders (not otherwise than to see is given willing to imitate Nature, we set sulfur on fire , and the vapor of it we recover by some vessel full of water through some interval of time) which afterwards the menstruum escapes, according to the said requisite operation. By this the menstruum or solvent (whatever at last by name it pleases to be called) has so great strength, which should be able to dissolve copper or iron (in the same manner by which aqua fortis divides & frees silver) as the very one by experience daily by us in the spirit of sulfur clearly indicates. Therefore when that menstruum, largely the place, which mineral of copper or iron is close at hand comes through crossed over, then for us certainly we are obliged to persuade, and also to the same time to be dissolved some portion of it (copper, or iron), truly of such size, of what size a second portion of sour spirit (acidus spiritus), which in itself is, to dissolve is suitable and powerful. What in fact you will see somewhat behind the fluid thereupon some green or yellowish to come forth, of the smell of metal & sulfur ; of sharp or rather sour & astringent taste : out of which liquid we separate and congeal that vitriol, which is this essential body (corpus), about which we make the present discussion. 89

Sala develops these ideas even further in a way that seems curiously similar to Van Helmont’s approach to reactions involving the esurine salt. As Hooykaas summarizes Sala’s views:

All changes leading to a really new substance according to Sala are ‘transmutations’ or ‘transsubstantiations’ in which the original substances are destroyed, just as in Aristotle’s true combination. To all other changes the names of ‘conjunction’ and ‘reduction’ are given. In the latter case a substance was only divided into little parts (e. g. when gold is dissolved in aqua regia) and by reunion of these particles (e. g. by means of a piece of silver) they are reduced to their former state.

The corrosives (acids) do not even destroy the base metals; their metallic character is hidden, not lost, in acid solutions; the metal is only divided into ‘tiny atoms’; there is not a transmutation but only a conjunction of the metal to the solvent. 90

The same opinion about metallic solutions we meet in van Helmont’s opus. Of course not only copper sulphate but all metal salts are to Sala aggregates, for they may be obtained by crystallization from solutions of metals in acids. 91

By men like Bodin and Basso, who rejected the authority of Aristotle, the conclusions obtained by experiments with solutions of metals were extrapolated to all other reactions: they considered every compound to be an ‘apposition of particles’. Their aristotelian opponents, inasmuch as they were not blinded by philosophical prejudice but were willing to listen to experiment, were gradually forced into the same position. 92

Conjunction

According to Hooykas, Sala says that

natural vitriol is only an ‘apposition’ of particles of copper, acid and water. It is an accidental being, not an essential unity. Common salt however, which he is not able to decompose, he considers a true unity under a substantial Form; it has a special essence fixed by the Creator in the beginning, whereas Vitriol is only ‘one by chance’. 93

In Sala’s words,

Omnia enim corpora quae salium nomine censentur, non solum modo differunt odore, colore, gustu, & aliis proprietatibus, a Vitriolo: sed & corpora simplicia ac incomposita habenda sunt, si cum Vitriolo comparentur, quae ipsa producta generataque sunt singula ex proprio suo peculiarque Ente, quod mirabiliter creatum, destinatum & ordinatum fuit in istum finem a nostro Creatore, a principio mundi, haud secus ac alia omnia semina & Entia reliquarum quarumcumque Rerum. E converso, Vitriolum (quantumuis procedat a prouidentia Summi & Aeterni Creatoris, ad humani generis bonum) non est corpus aliquod procedens a particulari aliquo Ente, ad ejus productionem destinato : sed est corpus quoddam accidentaliter constructum, ex concursu coincidentiaque diuersarum rerum , simul & eodem tempore ac loco.” 94

Indeed all bodies that are thought nominally of salt, not only differ in the manner of smell, color, taste, & other properties, from vitriol: & yet the simple and incomposite bodies will be considered, if with vitriol they are compared, that themselves brought out and begotten are one out of its particular and peculiar being (Ens), which miraculously was created, arranged & ordered in that land by our Creator, from the beginning of the world, and by no means all other seeds [semina] & beings [Entia] and with the rest of things. As a result of convert, Vitriol (as long as it proceeds by the providence of the Highest & Eternal Creator, according to the good of the human race) is not some body proceeding from some particular being [Ens], toward production of the same according to a previously determined plan : but it is a certain body accidentally made, out of conjunction/juxtaposition [concursus] and coincidence [coincidentia] of diverse things, likewise at the same time and place.

<to be continued>

Notes:

- On the debate, see also D. Thorburn Burns and Hendrik Deelstra, “Analytical Chemistry in Belgium: An Historical Overview,” Michrochimica Acta 161 (2008): 44-5; Debus, Chemical Philosophy 2: 306. ↩

- Halleux 94, 96-7. See also Ducheyne 306. ↩

- Halleux 96-7. ↩

- Van Helmont, Oriatrike 759. ↩

- Van Helmont, Oriatrike 770. ↩

- See, e. g., Partington 2: 209-243; Walter Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982); Debus, Chemical Philosophy 2: 295-379; Antonio Clericuzio, “From van Helmont to Boyle. A Study of the Transmission of Helmontian Chemical and Medical Theories in Seventeenth-Century England,” The British Journal for the History of Science 26 (3) (Sep. 1993) 303-34; William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe, Alchemy Tried in the Fire: Starkey, Boyle, and the Fate of Helmontian Chymistry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002); Steffen Ducheyne, “A Preliminary Study of the Appropriation of Van Helmont’s oeuvre in Britain in Chymistry, Medicine and Natural Philosophy,” Ambix 55 (2008) 122-35; Roos, The Salt of the Earth 47-107. ↩

- Ducheyne 305-7. See also John Ferguson, Bibliotheca Chemica, Vol. 1 (Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons, 1906) 381. ↩

- On the influence of Paracelsus on Van Helmont, see Douglas McKie, “Chemistry in the Service of Medicine: 1660-1800,” Chemistry in the Service of Medicine: 1660-1800, ed. Frederick Noël Lawrence Poyner (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1963) 43-54; Hugh Trevor-Roper, “The Paracelsian Movement,” Renaissance Essays (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985) 149-199. ↩

- Partington 2: 211-2; Pagel, Joan Baptista Van Helmont 8-10; Debus, Chemical Philosophy 2: 303. On the weapon salve controversy, see Edward Eggleston, The Transit of Civilization from England to America in the Seventeenth Century (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1901) 58-60; Halleux 97-8; Camenitzki 83-101; “Weapon Salve”, The Scientific Revolution: An Encyclopedia, ed. William E. Burns (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001) 320-321; Mark A. Waddell, “The Perversion of Nature: Johannes Baptista Van Helmont, the Society of Jesus, and the Magnetic Cure of Wounds,” Canadian Journal of History 38 (2003) 179-97; Bruce T. Moran, Andreas Libavius and the Transformation of Alchemy: Separating Chemical Cultures with Polemical Fire (Sagamore Beach, MA: Science History Publications, 2007) 271-289. ↩

- Pagel 9-10. ↩

- Pagel 1, 11-12. ↩

- Bruneel 234. ↩

- Pagel 12. ↩

- Debus, Chemical Philosophy 2: 306. Van Helmont’s pamphlet itself is very rare. De Heer complained he could not even find a copy of the pamphlet three days after it was put on sale. See De Heer (1635) A3; Albin Body, ed., Bibliographie spadoise et des eaux minérales du pays de Liége (Brussels, 1875) 14. There has been some confusion over the centuries whether Van Helmont published a separate pamphlet, Paradoxa de aquis Spadanis, in 1624. The evidence suggests Van Helmont published only one pamphlet on Spa waters which scholars have occasionally erroneously titled Paradoxa, perhaps because Supplementum is divided into seven “paradoxes”. Albin Body, ed., Bibliographie spadoise et des eaux minérales du pays de Liége (Brussels, 1875) 14-15. The pamphlet was later republished without any change in Ortus. See Halleux 100n22. ↩

- Heer (1739) 7-10. ↩

- Heer (1739) 7-10. ↩

- Pagel 50. ↩

- Van Helmont 688. ↩

- Van Helmont 688. On Syrach, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sirach. On the importance to Van Helmont and other Paracelsians of strict literalism in applying the Bible, especially Genesis 1, to the interpretation of natural phenomena, see Norma E. Emerton, “Creation in the Thought of J.B. Van Helmont and Robert Fludd”, Alchemy and Chemistry in the 16th and 17th Centuries, ed. Piyo Rattasi (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 1994) 85-101, esp. p. 85-87. ↩

- Van Helmont 688. ↩

- Pagel 50-1. See also Emerton 93-4. ↩

- For an overview of Van Helmont’s criticism of Aristotle, see Pagel 35-46. ↩

- http://www.classicreader.com/book/1789/4/ ; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phaedo ↩

- Van Helmont 688. ↩

- Emerton writes that “The existence of the subterranean abyss was taken for granted by most seventeenth-century writers, not only on Biblical authority but also on the assertion of Plato”. See Emerton 94. ↩

- Pagel 49-50; Emerton 88. ↩

- Pagel 50, cites Elementa, 4, Opp. p. 50. See also Emerton 92. ↩

- Pagel 50; Debus, Chemical Philosophy 2: 340; Emerton 93. ↩

- Pagel 51, cites Supplementum de Spadanis fontibus, III, 1, Opp. p. 649; Oriatrike, p. 693. ↩

- Pagel 51, cites Supplementum de Spadanis fontibus, I, 4, Opp. p. 645 and I, 20, p. 646. Ibid., I, 21, p. 646; Oriatrike, I, 20, p. 690, with ref. to Ecclesiastes, I, 7. Aqua, II, Opp. p. 56 and Supplementum de Spandanis fontibus, I, 17, p. 646. ↩

- Ducheyne 316, cites Oriatrike p. 108-9. See also Thomson, History 1: 182-3; Halleux 93; Ducheyne 316-7; Emerton 92-93. On precedents for van Helmont’s tree experiment, see Herbert M. Howe, “A Root of van Helmont’s Tree,” Isis 56(4) (1965) 408-19. ↩

- Van Helmont, Oriatrike 692. Curiously, Van Helmont in refuting Aristotle and De Heer always refers to a “constriction” of the air, whereas Aristotle (as quoted by De Heer) and De Heer himself consistently refer to vapors becoming waters due to a “cooling” of the air — which Van Helmont himself admits. If a careful reader restricts De Heer’s theory to what De Heer says rather than what he claims Aristotle said, De Heer does not actually say that much different than Van Helmont. ↩

- Henrici ab Heer, deplementum supplementi de Spadanis fontibus, sive vindiciae pro sua Spadacrene : in quibus Aroph, certissimum Paracelsi ad calculos remedium sincere explicatur (Liége, 1624). De Heer’s pamphlet I have not seen at all, so all I know is second hand, apart from a limited discussion of his disagreement with Van Helmont in later editions of Spadacrene. See also Debus, Chemical Philosophy 2: 307; Burns and Deelstra 44. ↩

- De Heer (1635) A3; Albin Body, ed., Bibliographie spadoise et des eaux minérales du pays de Liége (Brussels, 1875) 14. ↩